By: Chris Warren.

I was scrolling through my daily reads and was pleasantly surprised to discover that my good blogging neighbor Hugh over at Hughes Views & News honored me on his website! In his very flattering shout out he asked, “I’m hoping (Twenty First Summer ) will write a post about why the number 11 is not pronounced onety one?” I’m certain that was not a question for which Hugh expects a real answer, but I’m going to take on the job and give him –and everyone– a real answer because etymology does not get nearly enough emphasis in modern schools. That’s unfortunate, because if it did, we’d have a much more literate population.

Answering Hugh’s question requires a little backtracking to why 11 is not expressed as “one-teen” (the same idea applies to the number 12). Today we use a number system based on 10, but in post-Roman empire Europe, the number system was based on 12. That there is no -teen suffix for the next two numbers after ten is a leftover still surviving in modern English.

In Old English, the terms enleofan and tweleofan literally meant “one and two leftover” (from ten), respectively. The words eleven and twelve are their direct descendants. The teen numbers begin the next cycle. The modern suffix -teen, by the way, has origins in various forms in several early European languages and means “more than ten”.

That’s the quickie two paragrpah answer to Hugh’s challenge. The bigger matter beyond his quip is why etymology and its cousin, linguistics, are obscure sub-specialties that even most college English departments don’t take very seriously. These topics should be regular curriculum starting in kindergarten.

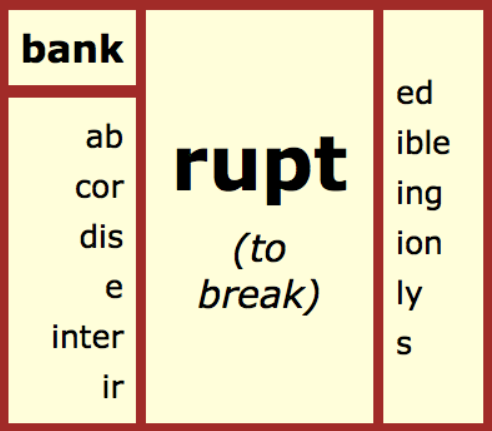

Most people learn words one by one (remember those dreaded vocabulary words in grade school?). It’s effective for what it is, but not very efficient. If instead one learns the original roots and fragments, then knowing all the words that come from them will become second nature.

Words that are related by etymology to the same root or have a commonality between languages are known as cognates. People with large vocabularies seldom attain such a high level of fluency by memorizing words one by one, as if reading a dictionary. They learn the various parts and pieces of words, then stick them together to make full words, or cognates. They may also go in reverse by reducing a cognate down to its origin to come up with a meaning.

A root term can have dozens of cognates, so it is much more effective to learn one root and extrapolate it out than learn each variation of the word individually. This is why learning cognates is stressed in foreign language courses. There is also such a thing as false cognates, but that discussion will have to wait for another day.

Now that we’ve humored Hugh and dipped our toes into the deep end of the language pool, the real question is, “How can one expand their literacy with etymology?” The answer isn’t complicated, but does require some effort and dedication.

First, do a lot of reading, preferably at or just above your reading level so you will be challenged. When you come to a word you don’t know, look it up in an etymological dictionary (yes, such a thing exists!). Take a moment to study the fragments and roots of the word as opposed to only the word as a whole. When you come across another word with the same components, try to derive the meaning based on what you know about the etymology of the term. Second, make an effort to use the new words you learn in your written and spoken interpersonal communications. Remember, context counts!

I know this all sounds tedious and slow, but with practice, you will be amazed at how fast your fluency and skill increases. The more you do it, the more seamless the process will become. The benefit is threefold: Larger vocabulary, greater reading comprehension, more effective interpersonal communications. Whether you are a high school student, a multi-degreed scholar, or a small time blogger (like me!), anyone can better themselves with etymology.

Regrettably, the day when etymology and linguistics are taught to grade schoolers is not on the horizon. Until then, I feel like one tiny little voice trying to convince others that obscure English department sub-specialties are worth the effort it takes to learn on your own.

Thanks for asking, Hugh! I hope my answer leaves you and everyone in a better place.