By: Chris Warren

All languages are orphans. What I mean is that none of them can trace their pedigree back to any single source or person. There is an exception: English, specifically, the version of it spoken today. While it is technically true that no one “invented” the English language, the way English speakers express themselves would be very different but for the works of William Shakespeare, who died 400 years ago this month and coincidentally was also born in April.

Shakespeare was respected in his time, yet he was not particularly well known outside of London and was not recognized as a literary giant until well after his death when scholars revisited his work in the early 1800s. By the late 1800s he was a bona fide legend; starting in the 1900s and extending until now, William Shakespeare has been a major component of high school literature courses and there are entire college degree programs dedicated exclusively to him.

A lot of information about William Shakespeare’s personal life is missing. His exact birthday is unknown, and no one living today is even sure what he looked like. He never sat for a direct formal portrait; the familiar pictures of him were created from second hand descriptions given by people who knew him. Shakespeare’s unintentionally mysterious life adds to the intrigue and legacy of his writing.

His words are reflections in a literary mirror reaching out across the centuries.

So why should modern day people like us care about the ideas of some scribe who’s been dead for four centuries? After all, we live in the internet age where trends and fads can have a shelf life of just a few hours, sometimes less.

Pop culture trends are indeed ephemeral. Four hundred years from now, no one is going to care about Kim Kardashian’s tweets. Shakespeare did not say things for the purpose of being popular or seizing a moment. He spoke of anger, jealousy, love, hate, sadness, joy, sorrow and every other possible emotion in a way that is ageless.

Because William Shakespeare’s language of emotion is universal, we can find ourselves in passages from Romeo & Juliet or Othello or any of the other plays & sonnets. His words are reflections in a literary mirror reaching out across the centuries. Anyone who even casually studies Shakespeare will eventually arrive at that moment of enlightenment when they exclaim to themselves, “Hey! He’s talking about me!”

It’s exciting to read literature from so long ago and feel as if the author knew us personally. William Shakespeare created a magic formula of words that never becomes obsolete because culture constantly changes but the human condition does not. Anger is the same as it was in the late 1500s. So is love, jealousy, and all the rest. Shakespeare took what is common to all people across all ages and gave it a voice.

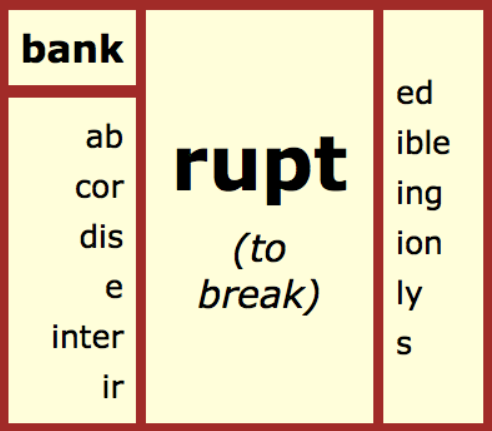

Interpreting emotion with such startling permanence would alone have made William Shakespeare the Greatest of the Great, but he did not end it there. He wrote 37 plays and 154 sonnets and from that body of work came thousands of words and phrases that we contemporary English speakers use every day without realizing their origins.

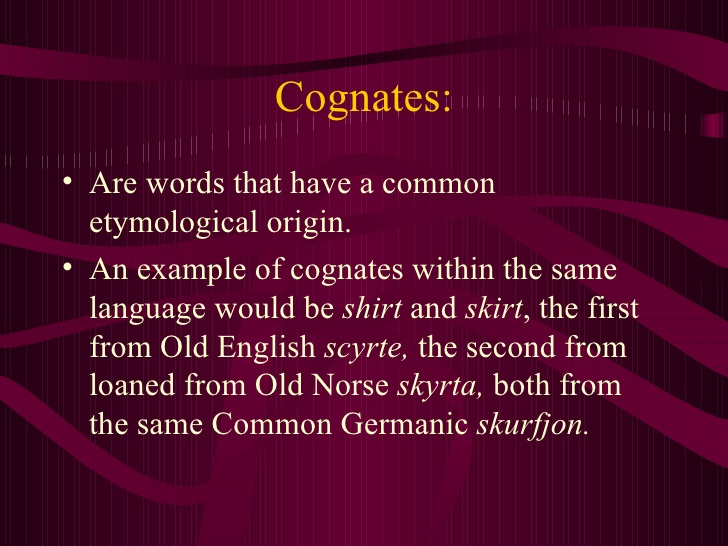

No single person has contributed anywhere near as much to the English vocabulary. If we removed all remnants of Shakespeare’s endowment to English, it would be immensely less diverse and would arguably not be the globally dominant language it is today. No other language has so many ways to express the same idea, and William Shakespeare is one of the reasons why.

Shakespeare does not make Shakespeare great. Humanity makes Shakespeare great. We, us, supplied the raw materials. All he did was identify the greatness and provide the conduit that converts it into language.

There is a little bit of William Shakespeare in every statement you utter and every sentence you read, as well as every feeling and emotion you experience. For sure, Shakespeare did not invent the the English language, but his literary DNA is inextricably woven into it in a way no one else’s is. That’s why no one can get away from him even if they don’t know him. That’s why Shakespeare still matters.